In “Advanced Readings in D&D,” Tor.com writers Tim Callahan and Mordicai Knode take a look at Gary Gygax’s favorite authors and reread one per week, in an effort to explore the origins of Dungeons & Dragons and see which of these sometimes-famous, sometimes-obscure authors are worth rereading today. Sometimes the posts will be conversations, while other times they will be solo reflections, but one thing is guaranteed: Appendix N will be written about, along with dungeons, and maybe dragons, and probably wizards, and sometimes robots, and, if you’re up for it, even more. Welcome to the third post in the series, featuring a look at Hiero’s Journey by Sterling E. Lanier.

This is a solo adventure this week, with Mordicai coming in next time to give his own take on something else from Appendix N, but before I get started, let me transcribe a conversation that occurred at a recent trip to a water park with my family. It was a scorching hot day, and we took the trip with some family friends. Four adults, five kids. While they were splashing around in the waterslides, I spent an hour or two relaxing by the wave pool and reading a paperback book from 1973.

My wife and my friend saw me reading and started talking about books they were enjoying at the moment—mass market best-sellers and romance novels I didn’t recognize by their titles.

“What are you reading?” my friend asked me.

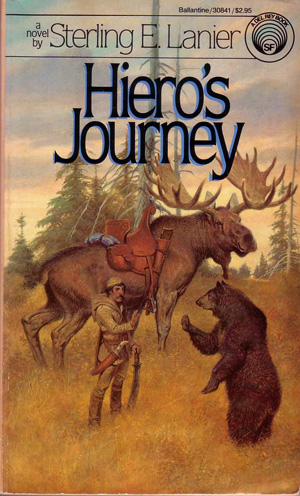

“It’s a book from the Seventies about a guy with a mustache who rides a giant moose and has a bear companion and fights mysterious forces after the apocalypse with his psychic powers.”

“Oh.”

That was the end of that conversation.

Yes, as you may have guessed—probably from photo above rather than actually having read the work of Sterling Lanier yourself—I was talking about Hiero’s Journey, one of the many books listed by Gary Gygax in his legendary Appendix N.

It may not sound like your typical proto-D&D fantasy novel, but that’s because it’s not. It’s also an incredibly enjoyable book. Lanier may not be even close to as famous as Robert E. Howard, Jack Vance, or Roger Zelazny or some of the others from Gygax’s list, but Hiero’s Journey constantly surprised me with its inventiveness and slow built toward a satirical climax.

It also moves with a pace appropriate to a story about a guy riding a giant moose and unleashing the occasional psychic fury on mutated howler monkeys and other nefarious creatures. That is to say that it’s not a swift-moving novel at first—Lanier builds his world through careful exploration by his protagonist—but it accelerates as the hero moves closer to the coast and the threats become imminent.

Lanier’s books are likely long out of print, and out of the originally-projected three volumes of the Hiero cycle, only two were ever written and published. (But Hiero’s Journey has a beginning, middle, and end, so don’t worry about closing the book unsatisfied.) He is probably best known—if he’s known at all—for being the editor who brought Frank Herbert’s Dune series to publication, but he was fired for it, because Herbert’s work wasn’t an immediate success. Or maybe some know him for his sculpture work, crafting miniatures that have been displayed at museums.

Reportedly, he sculpted miniatures for J. R. R. Tolkein’s Lord of the Rings, but Tolkien asked that they not be commercially distributed. The internet isn’t rich with sources for some of this information about Lanier, and that tells me that he’s largely been forgotten. I mean, people will write comprehensive histories about minor characters from a single episode of Cheers on the internet, but information on Sterling Lanier seems to come from few sources, and all the sources seem to quote each other.

So perhaps there’s a story about Sterling Lanier worth telling, more facets to his life that have yet to be revealed, but I don’t know anything about him other than what little I’ve seen online.

But I know that Hiero’s Journey is not only a great example of early-1970’s genre fiction, and a heck of a fun read, but it’s also a book that seems to have informed one of the weirder seemingly-slapped on aspects of Dungeons & Dragons—I’m speaking about psionics, which seemed out of place in the original AD&D Dungeon Master’s Guide—and almost the entirety of the later Gamma World game setting.

Gygax isn’t credited with designing Gamma World, but James Ward’s original rulebook for Gamma World cites Hiero’s Journey as an influence, and with that game’s post-nuclear-holocaust setting and mutated animals and cities with names like primitive spellings of our own, it’s like playing scenes straight out of Lanier’s novel.

Let’s jump back to the D&D rules and psionics a bit, because I have always found that to be a curiosity in the Dungeons & Dragons world. It always seemed like a high fantasy world with spellcasters like wizards and clerics didn’t also need psychic powers and mind blasts. Because much of my early exposure to fantasy fiction was the Tolkein and C. S. Lewis, or the books that were thrice-removed cousins of those classics, I always wondered about the psionic rules. It didn’t seem like a medieval Professor X was a good fit for the standard D&D setting.

But in Hiero’s Journey, the power of the mind is the most potent power of all, and as the absurdly-named Per Hiero Desteen explores the hinterlands, he hones his psychic powers in a way that represents his growth as a character. It fits here, as a power set, and provides a new context for me as I think about the exploration and character-growth aspects of the Gygax-written AD&D rules.

Perhaps it fits better in a post-apocalyptic landscape then in the frolicking faerie realms of D&D, but there’s also a school of thought that says all Dungeons & Dragons games take place after the fall of some great empire of the past. After all, those millions of intricate dungeons and tombs had to come from some once-great civilization now fallen on hard times. The more I read from the Gygax Appendix N list, the more I realize why D&D is a more ambitious genre mash-up than just Gandalf meets Conan.

What else do you need to know about Hiero’s Journey, other than the bits about the mutated animals and the post-nuclear setting and the psychic powers?

Know that it’s written as a wilderness adventure tale first, and everything else second (well, at least for the first two thirds of the novel). Per Hiero Desteen is like a character out of an episode of Grizzly Adams, a wandering priest sent into the forest. But he’s also labeled a “Killman,” a kind of elite super-agent of the Abbey, only he doesn’t seem like he knows what he’s doing and he mostly bumbles along with the help of a mind-reading bear and an escaped princess who pretends to be a slave girl.

It’s incredibly charming, all of it, in its telling and in its before-green-was-cool political messages about what we are all doing to our own planet. (Sure, Earth Day was a thing in 1970, but it was ignored for the next 20 years. Sterling Lanier didn’t ignore it, I’m sure, but everyone else did.)

Most of these Appendix N books are pure imaginative fantasy with maybe some symbolic statements about the way we treat others or some archetypal good and evil clichés, but Hiero’s Journey hammers home the point—slowly, but steadily—that a lot of the fantasy and science-fiction novels written in this country (or just a lot of that genre stuff in general) is relatively thinly-veiled commentary on the state of the world as the book’s being written.

Hiero’s Journey has the foreboding of the Death (which we can quickly deduce as a thermonuclear event of some kind, occurring in the distant past of the story), and we can see the parable of the Brotherhood of the Eleventh Commandment, kindred spirits to Hiero, who advocate for preservation over destruction of our natural resources. They are Earth-Firsters, in the future, as a religion.

To be honest, I normally don’t have much patience for such heavy-handed messages, but because Lanier tells the story so well, and makes Hiero’s exploration so full of life and passion and mystery, the pro-environmentalist agenda of the book never feels grating. It feels like an important layer to the story, but that’s okay, because it makes its point because of the story rather than using the story just to further its point. Lanier seems mostly concerned about Hiero and his companions and their ingenious survival methods, and the social commentary is secondary.

Until the climax of the novel.

Then, Lanier perhaps goes too far in his satire, but I still enjoyed it.

What Hiero and his companions find, as they explore and escape capture from the new breed of machine-friendly beings who don’t seem to recall what trouble technology hath wrought, is a deep and treacherous dungeon. This part is almost pure D&D adventuring, with roving monsters (mutated beasts) and foul threats from below. But what the dungeon turns out to be, though Hiero doesn’t have the words for it, is a nuclear launch bunker. The characters are deep beneath Washington D.C. and they’ve found the technology that has destroyed our civilization to make way for their own.

For Hiero, it’s information, but we see the political commentary in the description of what remains of our current (in 1973 or today) government. Oh, and one more thing, there’s a kind of proto-Borg like creature that prowls the underworld in the latter sections of the novel. Something that’s fungal and inclusive and filled with psychic power. This hive-mind that can paralyze beings with mere thoughts? It’s so massive the characters in the novel call it the House.

It’s the House. And it promotes inaction with its group-think. In Washington. Get it?

I’m pretty sure you can read the novel and completely ignore that satirical angle and enjoy it as a meditative adventure story in some North America thousands of years in the future. Or you could do that and chuckle at Lanier’s quaint-but-still-sadly-true political and social commentary.

No matter how you approach Hiero’s Journey, I still say it’s worth reading. I’ve only spoiled the beginning and end for you. There’s plenty of goodness to be found in its pages.

Come on, it’s about a guy with a mustache who rides a giant moose and has a bear companion and fights mysterious forces after the apocalypse with his psychic powers. That description may not have impressed my water park companions, but I’m sure it’s just a matter of time before they ask me to borrow my copy of the book. It’s definitely unlike anything else they’ve read this year or probably ever.

Tim Callahan usually writes about comics. Mordicai Knode isn’t here this week to talk to him about how great Hiero’s Journey turned out to be, which is his loss, really. Maybe they can get together for a Gamma World game sometime and all will be right with the world.

Actually, both Journey and Unforsaken are available in Kindle and Nook editions; I’ve no idea as to the provenance or quality of the digital editions.

I have always wondered about this book while perusing Appendix N and now, based on this article, I must have it for my collection. It sounds fascinating and so deliciously weird. Also, it sounds like it may have informed the D&D druid class a bit too in addition to psionics and Gamma World.

Definitely grabbing a copy of this and the sequel.

I read Hiero’s Journey back in the 70’s or 80’s and it still stands out as one of my favorites at that time of my life. I’m tempted to re-read it but fear my copy will fall apart – maybe I’ll go for an eBook version instead.

Oops, double post!

I found a copy of this book and once I saw “telepath” and “moose” on the back copy, I was sure this was going to be a so-bad-it’s-good read. Instead it was passable. It’s the kind of book that sets your expectations way down and then pleasantly surprises you.

Ethan

My favorite Lanier book in the 70s was The Peculiar Exploits of Brigadier Ffellowes, a book of tall-tales-told-in-a-club (like Dunsany’s Jorkens stories, and somewhat like the bar stories of Pratt & De Camp, Arthur Clarke and Spider Robinson). But Hiero’s Journey was on my list of frequent rereads. I had a look at it fairly recently and it held up pretty well, though there were some eyebrow-raisers.

Lanier also wrote a planetary adventure, Menace Under Marswood. I thought it was surprisingly bad–to the point of being inept. Never reread it.

Both of the Ffellowes books are on Kindle, but I’d recommend seeking out print versions. They’re some of the worst-formatted ebooks I’ve ever seen.

I was surprised to see this on the D&D list, but in a pleasant way. There is a lot of this book that is very much of its time. Psychic powers were all the rage back then, with Andre Norton, Murray Leinster and others writing tales of folks with psychic links to animals. And surprisingly enough, this infatuation with psi was led by John Campbell, editor of Astounding/Analog, the hardest of hard SF guys, who was publishing a lot of tales like the Telzey Amberdon stories of James Schmidtz. And there were also a lot of post-apocolyptic tales with a wandering warrior floating about, John Dalmas’ Yngling tales among them. But Lanier put all these elements together with a lot of wit and panache that made this book a personal favorite of mine. He definitely deserved more attention than he got during his short career. I even liked the satire. Being of college age, it was not too broad for my taste at the time.

Lanier was also the author of the Brigadier ffellowes stories, which were really nicely-done excursions into, mostly, cryptozoology. I actually preferred these to the Hiero books, but the latter were pretty good, for the most part – a bit too much reliance on the unlimited transformative power of radiation-driven mutation (giant loons? chasing off giant lampreys? honestly) (and too many of his mutant fauna were just giant versions of modern species), but still good adventures.

Oh yes this. It’s Hiero’s Journy and Unforsaken Hiero are two of my guilty pleasure reads. And I’ve missed them since I had to give up my library of books when I moved 15 years ago. Anyway back to Hiero it is a fun guilty read and I’m glad to find that it is available as an ebook on Amazon.

Oh and Gygax didn’t only get psionics from Lanier. He also got it from Andre Norton. If you look you’ll notice he didn’t list any one book of hers or any one series but instead just lists her. All of her space books have psionics as an element, but surprising to anyone who doesn’t know is that psionics are just there as part of her fantasy world. As a matter of fact she even has one book that explicitely recognizes this. The recently rereleased Wizard’s World that starts with an esper on the run from a pack of psi hunters who passes through a gate to a world with magic and psionics.

I don’t have a copy of the DM manual to check, but were Robert Adams’ Horseclans books in there?

As a wise man would say: ’nuff said.

I remember this book and its sequel, but no specifics, just “cool.” I wonder if it’s somewhere in the mass of unorganized books in my basement? I don’t remember having seen it recently, so think I let it go in a move sometime in the past 35 or 40 years.

But I may have to check out the ebooks.

“Sure, Earth Day was a thing in 1970, but it was ignored for the next 20

years. Sterling Lanier didn’t ignore it, I’m sure, but everyone else

did.”

Um, not really.

The Unforsaken Hiero was one of my favourites as a kid. I read the original afterwards, still liked it but not as much. (I also bought Gamma World before I ever played D&D, and the influences are obvious.)

Both Hiero books were staples of my youth (along with countless Moorcock books). Will have to excavate my paperbacks and give them a re-read.

I started reading Hiero’s Journey last night and so far it’s as awesome as the blog post made it out to be. One interesting tidbit, the protagonist is a PoC (he’s Metis from what was once Canada).

Bought Hiero’s Journey off the internet after I first read this post back in June (2013). Just finished the book tonight (7-14-13) and loved it! I had never heard of this book or its author. It seemed highly innovative for a 40 year old book! I’ll have to track down the sequel now.

I bought the sequel today for $1.50!

> people will write comprehensive histories about minor characters from a single episode of Cheers on the internet

The internet certainly has a blind spot in the things that went on before it’s wide adoption. Perhaps that will change if/when more documents get scanned and included in search engines?

I’m mostly sad that Lanier never chose to write the third book, even though he lived to 2007. I hold out the hope that he did write *something*, that it just needs to be found.

Found these blog posts while reading Hiero for the first time. Fun read. Some parts aren’t great.

Not sure but I believe the House might be the inspiration for Zuggtomy!